What Even is Mont-Royal?

April 20, 2023 | Montréal, Québec

If you’ve been in Montréal lately, you know we’ve taken an especially hard left turn into good weather.

Only a couple of weeks ago, we had a freezing rain storm that led to one tragic death and nearly a million people without power. Even with tree branches still on some streets in my neighbourhood, Montréalers are basking in the sunshine, and the Bixis are back on the streets—the surest signs of summer here. In response, I’ve been spending all my time outside, benefitting from the undeniable effects of Vitamin D. So has everyone else, at least at Jeanne-Mance Park, which has been bustling with people.

Like many of my neighbours, I often take a break from the city to enjoy nature at Jeanne-Mance or the bordering Mont-Royal. Of course, being one of the most iconic landmarks in Montréal, the “mountain” is a must-visit whenever friends or family come to see me. Whether enjoying the park with friends or playing tour guide, I’ve never previously given much thought to the design of the park. As it turns out, there is a vault of history to unlock. I’ve loved researching the park's history, and I hope you enjoy hearing about it in this blog post.

Photo credit: Harry Sutcliffe, courtesy of the McCord Stewart Museum.

Mont-Royal was not always a green oasis from the city. Though protected from industrialisation and urbanisation by the hospitals and cemeteries located at the edges of the land, it was not until 1874 that Frederick L. Olmstead was commissioned to design the park. Olmstead was a well-known landscape architect who had designed, among other projects, the famous Central Park in New York City. Olmstead strongly believed in nature as an “effective therapy against mental disease” (Murray 1967, 163). As a result, he imagined people would be “gradually and sweetly led up” the mountain and back down again, maximising the therapeutic benefits of nature for park patrons (Murray 1967, 167). Additionally, Olmstead thought that all parts of park design should coalesce under a single vision (Murray 1967, 166). While initially considered the site too rough and, thus, inappropriate for a park, he believed that he could transform Mont-Royal’s deficiencies into strengths supporting his vision (Murray 1967, 165-66).

“When I hear Olmstead’s vision for the park, I can’t help but intuitively agree with his principles. Anecdotally, sunshine and nature seem to do so much for my mental well-being on a bad day.”

Olmstead’s design principles are present in all parts of his original design. For example, though he acquiesced to the need for some roads into the park, he stressed that they should disrupt the scenery as little as possible by limiting their number, remaining natural, and winding slowly up the mountain (Murray 1967, 167). For instance, Olmstead argued that the city should construct the roads at such an angle that a carriage drawn by one horse (it was 1874, after all) could climb and descend the mountain easily without moving too quickly or too slowly (Murray 1967, 167). So, small details, like the intricacies of road construction, were designed with the slow journey through the park and the existing geological features of the site in mind.

Tragically for Olmstead, the city did not dutifully carry out his precisely thought-out design. When the park opened in 1876, it differed significantly from the original design. Olmstead was philosophically against certain constructions, such as some steep roads, cramped entrances, the unsightly reservoir, and tall stairs (Murray 1967, 171).

When I hear Olmstead’s vision for the park, I can’t help but intuitively agree with his principles. Anecdotally, sunshine and nature seem to do so much for my mental well-being on a bad day. I mean, I even wrote a blog post on getting out of the city to touch grass. Also, it makes sense that cities should design parks cohesively. I mean, would you want a disorganized experience? How Olmstead describes a languid journey through the park's beautiful scenery sounds idyllic, and he and I are not the only ones who think so. So many hospitals were built along the mountain due to the hygienist movement and its belief in fresh air for patients.

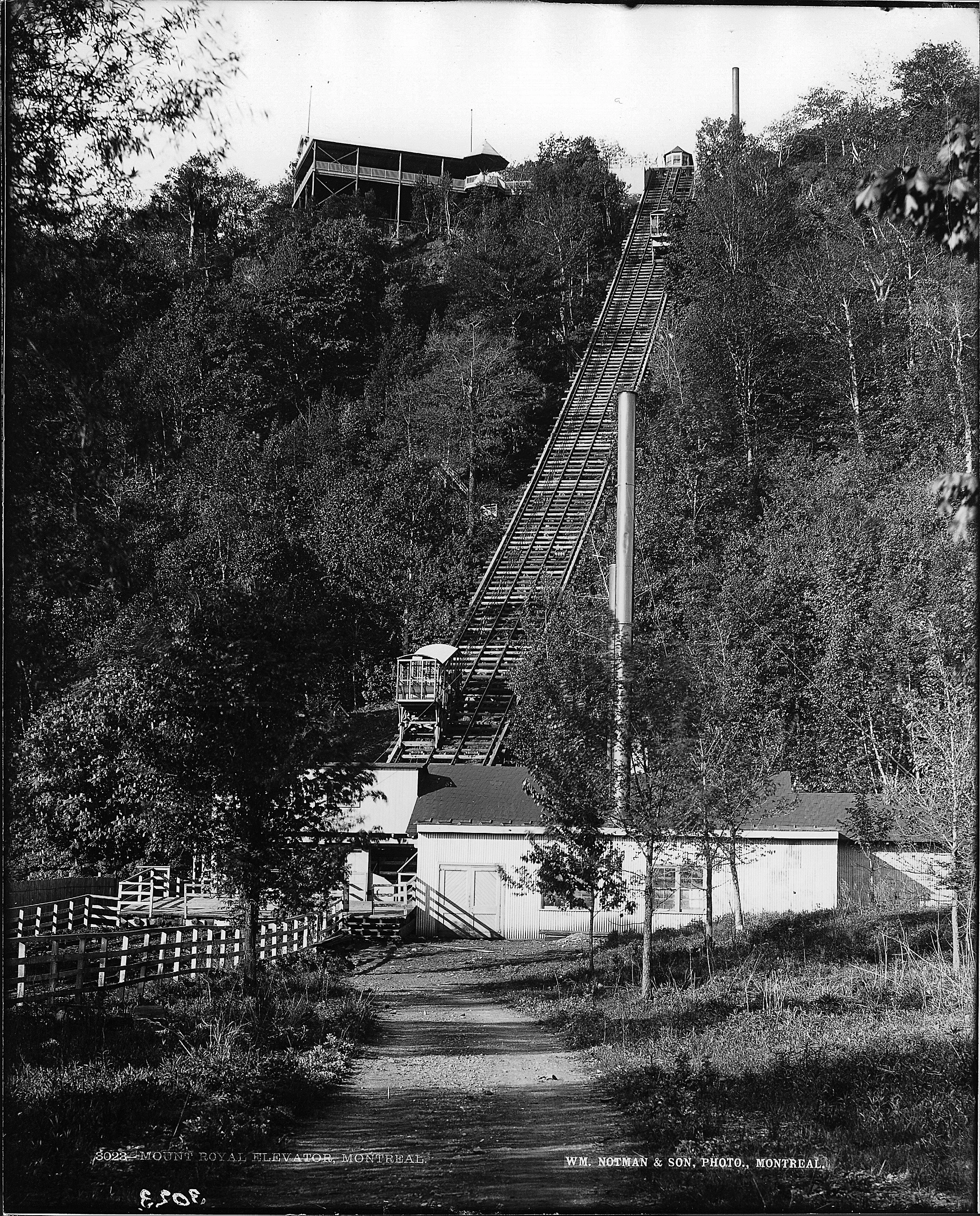

Nevertheless, Olmstead’s conviction in a leisurely journey up Mont-Royal was not universal. To improve accessibility, the Mont Royal Funicular Railway was briefly in service from 1885 until 1918, when it was declared structurally unsound. It crossed Olmstead’s gently slopped pathways, bringing visitors quickly and directly from Ave du Parc to the Olmstead trail and up to the top.

Photo credit: Wm. Notman & Son, courtesy of the McCord Stewart Museum

Olmstead brought a distinctly Victorian-era approach to park design. His story is about the philosophies and principles of one man. Fundamentally, he believed that shaping the park's design would shape the behaviours of park-goers, many of whose tendencies he sought to curb. He wrote about the park, “If it is to be cut up with roads and walks, spotted with shelters and streaked with staircases; if it is to be strewn with lunch papers, beer bottles, sardine cans, and paper collars and if thousands of people are to seek their recreation upon it unrestrainedly, each according to his special taste, it is likely to lose whatever of natural charm you first saw in it.” (Murray 1967, 166).

“He didn’t seem to realise that the park was much more than a tranquil green space. It’s also a community centre where people from the neighbourhood meet with their loved ones, families from all over the island spend a day, and visitors from abroad come to see the city.”

In many ways, Olmstead’s vision is directly at odds with how I and many Montréalers enjoy the park today. It strikes me that he much preferred the “natural charm” of the park to the people who used it. He must have never come out of the depths of winter to spend a lazy day surrounded by his neighbours. In criticising the food, the trash, and the noise people bring to the park, he must have forgotten the beauty of being in a community—a community of people enjoying green space together and apart. He must have never picnicked in the park or smelled others doing the same. He seemingly never scrambled up those steep stairs off Avenue Des Pins to look out over the city on a warm summer night. He certainly never enjoyed coming out of the forest to the sound of the Tam-Tams on a Sunday. He didn’t seem to realise that the park was much more than a tranquil green space. It’s also a community centre where people from the neighbourhood meet with their loved ones, families from all over the island spend a day, and visitors from abroad come to see the city.

Rutherford Reservoir.

Photo credit: Chloe Merritt.

Olmstead thought, “The forest was ruined by a zig zag road and city reservoir” (Murray 1967, 166). Well, that reservoir is one of my favourite places in the city. Now covered by a turf field, I’ve spent countless mornings practicing ultimate frisbee seeking my recreation upon it unrestrainedly, sweating, running, laughing with my teammates and watching the sun come up over Montréal. People play soccer, tennis, and football at Jeanne-Mance. People toboggan, ski, and snowshoe through the mountain. They use the park to bike, hike, and play.

Moreover, Mont Royal is still more than Olmstead’s green sanctuary or my recreational paradise. It’s a part of our shared history.

“Before Jacques Cartier named the mountain, or

Maisonneuve carted the first cross up to the top, it was part of the landscape and

an area Indigenous peoples called Tiohtià:ke.”

First, there are the Morality Cuts of 1954. During an ultra-conservative era in Québec politics and under the mayorship of Jean Drapeau, crews felled thousands of trees in an overgrown section of Mont-Royal. As a result of the Depression and poor funding, Olmstead’s curated green space had become an untended forest, nicknamed “the Jungle'' (Caron 2018, 41-42). The trees were cut “to reconstruct [the Jungle] as a heterosexual space” since without the tree cover, authorities could more easily police “undesirable persons … drunkards, criminals, sex maniacs, perverts, and most importantly, homosexuals” (Caron 2018, 39). The resulting photos of a bald-looking Mont-Royal are a good laugh. I wonder if Olmstead could have imagined how his park would be used. Even less likely is if he could imagine the oppression and discrimination gay Montréalers have endured. Mont-Royal provided geographic isolation and ecological cover from hate in the city, and the government responded by scapegoating and criminalising gay park visitors—yet another instance in the longstanding effort to erase the presence of Queer people (Caron 2018, 42). Despite the mayor’s best efforts, the 2SLGBTQ+ community maintains a vibrant, visible presence in Montréal. You can even explore a digital archive of gay experiences in Mont-Royal and the rest of the city on Queering the Map.

Grafitti on the corner of Avenue du Parc and Avenue Des Pins. Photo credit: Chloe Merritt.

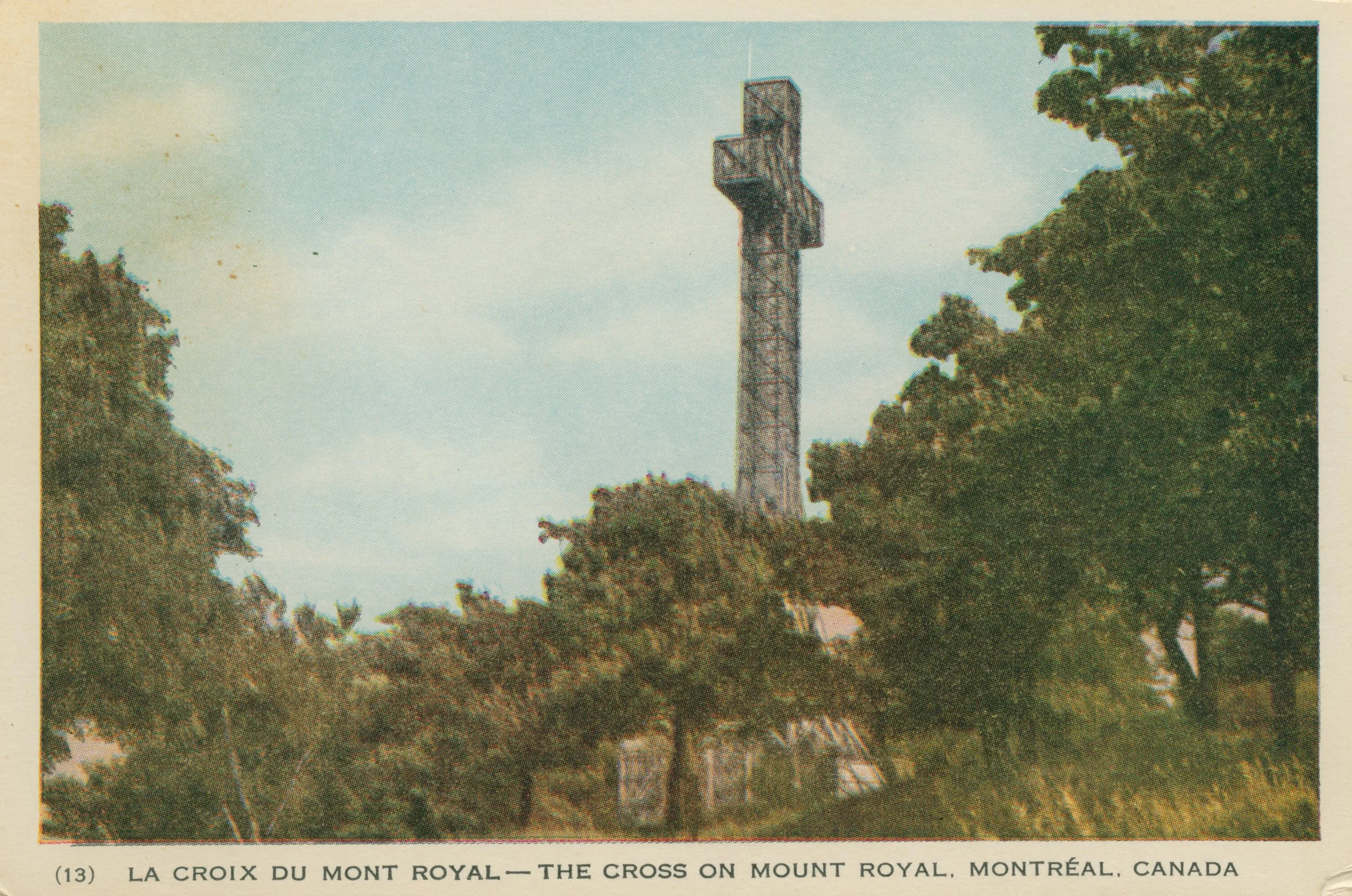

The mountain also continues to be a symbol of ongoing colonisation. Before Jacques Cartier named the mountain, or Maisonneuve carted the first cross up to the top, it was part of the landscape and an area Indigenous peoples called Tiohtià:ke. The mountain supported agriculture, provided wood for building, and housed a burial ground. The base of Mont Royal was the site of the Iroquoian village of Hochelaga, which was abandoned by 1600. Of course, Montréal/Tiohtià:ke, is located on Kanien’héka territory. The Mohawk people, as they are more commonly known, are the keepers of the Eastern Door in the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, an alliance of nations that spans large parts of southern Québec, Ontario, and parts of New England. However, the connection between Indigenous peoples and Mont-Royal is not merely the past. Just last year, Mohawk Mothers protested to remove the cross at the top of the mountain ahead of the Pope’s visit to Canada. Rather than symbolize Paul de Chomeday’s prayers to spare his colony from flooding or the unique history of the Montréal, the cross symbolizes the atrocities committed by the Catholic Church in the name of assimilation and cultural genocide.

No doubt, my latest party fact is that Olmstead originally designed Mont Royal; it's a great tidbit to share. At the same time, we can’t separate the park's history from Montréal’s history and its residents. Olmstead may have crafted the “perfect” experience of Mont-Royal, but the places we live begin to reflect who we are. I’m referring to Mont-Royal and the charging outlets on STM buses, the murals in the Plateau, and the terraces we build all over the city in the summer. The park may influence its visitors, but residents shape the park, intentionally or unintentionally, through their experiences. Whether they seek recreation in the park, expedite their trip through the mountain, escape from the city, or resist colonisation, they all leave their mark. Maybe Olmstead would disapprove of Mont-Royal today, but who cares? It’s not his anymore; it’s ours.

Main Photo Credit: Unknown artist, courtesy of the McCord Stewart Museum.

Author

Chloe Merritt

Community Liaison Lead

for Y4Y Québec